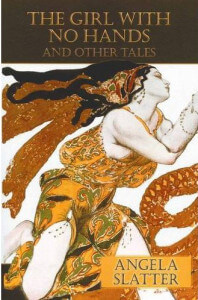

Title: “The Girl with No Hands & Other Tales”

Author: Angela Slatter

Genre: Fantasy / Fairy Tale / Lore

Pages: 210

Type: Collection

Stories: 16

—

What’s Friday Story Dissection?

It’s a weekly feature on the blog where I cast a more in-depth look into short stories, either in a collection or in an anthology. The idea is for these short stories to exist within the context of a loose narrative, determined by a theme, intent and story order intended by author or editor.

Anthologies have adopted detailed prompts to narrow down the wiggle space of submissions, thus creating a more focused narrative. I believe short story collections tell a larger story with individual stories feeding off and layering a top each other.

It’s my intent to break down stories to their elements – a detailed, spoiler-full review with the mandatory quotes as a base to speak about the short story collection/anthology at length. This is a practice Bulgarian literature teachers would implement, loosely translated as “analytical literary essay”, but on a much smaller scale. Plus, I intend to weave in personal digressions, so there’s that, too.

—

Stories Dissected:

[1] “Bluebeard”

[2] “The Living Book”

—

“The Jacaranda Wife” by Angela Slatter (3/16)

Let’s do this. Friday has arrived and it’s time to present the third story out of Angela Slatter’s “The Girl with No Hands & Other Tales” – “The Jacaranda Wife”. Compared to the first two stories – “Bluebeard” and “The Living Book” – this story is particularly quiet and meek (or as I would explain it; there are no outright murder or torture scenes).

“The Jacaranda Wife” foregoes physical violence, an intrinsic element to fairy tale narratives before the story form suffered brutal censorship, in favour of psychological torture. The story seems to follow a predestined happy-ever-after pattern of events. James Willoughby finds one day a woman of extraordinary beauty (the story describes the woman as ‘white-skinned as the moon, violet-eyed’), who appears to be mute and without any known relations to may come to her aid. The native tribes try to explain that this woman is born out of the jacaranda tree and that they ‘bring only grief’. However, their please fall on a deaf ear.

A wedding soon follows and Emily (a name and identity given to the heroine by James) finds herself the property of a man who thought he needed a woman of beauty and no will. This is just beginning and it just reinforces the themes from earlier stories – women are not in charge of their bodies or their lives.

In “Bluebeard”, Lily’s courtesan mother has made her fortune with her ‘pink matter’, while Sophia from “The Living Book” functioned as a sophisticated sex toy when Constantine ‘took me that way’. Slatter continues to demonstrate how effortless it is for men to exploit women’s sexuality and construct identities for their women as Willoughby is shown doing when he first gives the woman her name – Emily.

The name belongs to his grandmother, which already means he has expectations and a vision of how this dream girl should be as his wife. It’s easy for Willoughby to model Emily as she’s essentially trapped through the institution of marriage. At this point, the story reminds a bit of the Beauty and the Beast, but without any affection growing between the couple. Quite on the contrary as evidenced in gradual changes in Willoughby’s treatment towards Emily:

“She didn’t seem to care what he did to her body – having no experience of men, either good or bad, having no concept of her body as her own, she accepted whatever he did to her. For his part, he laboured over her truing to elicit a response, some sign of love or lust, some desire to be with him. Never finding it, he became frustrated, at first simply slaking his own lust, quickly. Gradually, he became a little cruel, pinching, biting, hoping to inflict on her a little of her hurt his love caused him.”

In a similar fashion to “Bluebeard” and “The Living Book”, the male character’s strength and authority erode the more he seeks to subjugate, dominate and control the female lead. Later in the story, Willoughby succumbs to the drink; dissatisfied and spoiled from an unsatisfactory marriage. Love has been long drowned and downed with the whiskey.

“For all the centuries men have dreamed of the joy of a silent wife, Willoughby discovered that the reality of one was entirely unsatisfactory.”

Yes, the jacaranda woman has brought grief to this house and its owner, but it’s Willoughby’s actions that caused all the heartache to begin with. Even when confronted with the true nature of his wife one day when he sees her sink through the bark of a jacaranda tree, he chooses to cling to his obsession even though it cost him his health and sanity. Willoughby orders to have every jacaranda tree cut – a desperate act to establish his authority, although by this point none remains.

Emily, although seemingly passive and devoid of any agency, demonstrates patience and stoic strength as she tests the walls of her prison. It is evident that Emily needs help to escapes, but it’s not a man that provides the tools for her salvation. Instead, it’s the hard-working and kind-hearted Mrs. Flynn who shows her how to return to her own world. Another excellent move to subvert the tropes.

“Martha shivered. She was terrified of this ghostly creature, but she hoped she loved Emily more than she feared her, loved her enough to show her the way back.”

It’s good and healthy to see two female characters who are not pitted against each other or are in a competition for looks, power or a man. Just two women who follow their hearts to do the right thing.

To me “The Jacaranda Wife” reminded me of the selkie and their tragic fates to live as human women so close to the ocean but never being able to return (not without their skins anyway). The connection is quite obvious as Slatter confirms her inspiration in the notes about every story and the fact Martha speaks about the selkie towards the end of the story.

Nevertheless, the transplant of these mythological creatures into such a drastically different environment was handled so smoothly, I actually believed there was a myth about jacaranda women hiding in the trunk – expat dryads or another female forest spirit indigenous to this particular flora.

However, as it turns out Australians have no folklore involving the trees in such a way as to suit the purposes of this story. This only proves Slatter’s knowledge and understanding of the fairy tale form to craft stories that grip the heart with the same intensity one of the mainstream classics would.

—

Chances are not many have come to this point. If you have and this has been something you enjoyed, please donate to my PayPal account. I’ve been reviewing books for more than five years now and this project takes a lot of time and effort. Any appreciation would be grand! If you can’t donate, like and share the post! Comment even.

Be First to Comment