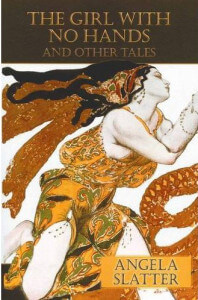

Title: “The Girl with No Hands & Other Tales”

Author: Angela Slatter

Genre: Fantasy / Fairy Tale / Lore

Pages: 210

Type: Collection

Stories: 16

—

What’s Friday Story Dissection?

It’s a weekly feature on the blog where I cast a more in-depth look into short stories, either in a collection or in an anthology. The idea is for these short stories to exist within the context of a loose narrative, determined by a theme, intent and story order intended by author or editor.

Anthologies have adopted detailed prompts to narrow down the wiggle space of submissions, thus creating a more focused narrative. I believe short story collections tell a larger story with individual stories feeding off and layering a top each other.

It’s my intent to break down stories to their elements – a detailed, spoiler-full review with the mandatory quotes as a base to speak about the short story collection/anthology at length. This is a practice Bulgarian literature teachers would implement, loosely translated as “analytical literary essay”, but on a much smaller scale. Plus, I intend to weave in personal digressions, so there’s that, too.

—

Stories Dissected:

[1] “Bluebeard”

[2] “The Living Book”

[3] “The Jacaranda Wife”

—

“Red Skein” by Angela Slatter (4/16)

“Red Skein” is the fourth tale from Angela Slatter’s breathtaking collection “The Girl with No Hands and Other Tales” and has become my favorite story as well as my favorite classic fairy tale retelling of all time. The story takes on the Little Red Riding Hood and preoccupies itself with heavy themes such as sexuality, societal acceptance and rejection, fear of change and the treatment reserved for those considered pariahs and outsiders.

Little Red Riding Hood has marked my childhood since an early age and continues to linger – a dark, dangerous story even when censored for children. Compared to other stories, which all dealt with how girls are punished, if they fail to adopt a certain behavior, Little Red explores universal fears and dangers – being lost, veering off the well-trodden path and being devoured metaphorically and literally. These are all possible, plausible, physical dangers coded into our blood and flesh.

Of course, it did help that the Big Bad Wolf cross-dressed to fool Little Red before eating her in a single bite. Even as a child’s story, the tale taps into our in-built self-preservation and gets our blood pumping with some good old-fashioned survival horror. I remember reading other versions where once freed the grandmother sews stones inside the wolf’s belly, who then falls into the river and drowns. The original story itself is fascinating and Angela Slatter herself has a go at it on her blog: Little Red Riding Hood – Life Off the Path.

It’s the one tale that lends itself to intuitive interpretations where Little Red assumes a more traditionally male role of a physical savior, who brandishes a weapon and vanquishes the big, bad wolf. She is more easily seen as a hero. She has been envisioned as a werewolf hunter as portrayed by Felicia Day in SyFy’s Red, a skilled swordswoman according to Deviant Art and a psychotic murderer in the Ever After webcomic.

“Little Red Riding Hood & Wolf” – artist unknown

It’s easy to imagine Red as the protector who keeps the danger at bay, but for Angela Slatter this would be too obvious. Instead of protector, she turns Red Riding Hood into the danger:

“As a boy watched, hard and panicked, he saw fur sprout over her limbs, saw her teeth lengthen and her jaw distend, saw her yellow eyes slit in lupine desire as the great wolf laboured over her. Unable to stop himself, the boy rose. His movement caught Matilda’s attention. She howled in fury and, with an effort, pulled herself from her mate.”

Yes, Red Hood (Matilda) is the wolf and she has no qualms about punishing those who, in her eyes, have transgressed – whether they belong to her village or not is irrelevant.

Her power has been coded into her sexuality. Her transformation into a beast and her own raw sexual energy have been linked on a primal level, entwined in her blood and under complete control. While the bodies and sexuality of the women in “Bluebeard”, “The Living Book” and “The Jacaranda Wife” were oppressed and the women had to find personal liberation, Matilda never had this problem.

Her body, sex and youth are hers to command. She is wild, mysterious and mesmerizing to all the boys in her village. But most importantly, she intimates:

“Village boys her own age would have liked to know what waited her skirts. They had tried to find out; some had worked up the courage to ask her to walk out with them, but when she turned her yellow eyes on them, their cool depths turned the would-be suitor’s knees to jelly and his heart to lead. Matilda smiled and walked on.”

“Red Skein” comes as a direct, jarring contrast to “The Jacaranda Wife” where Emily lived her life as a possession – passive and voiceless. Matilda, on the other hand, is dominant in her sexual relationships. She is the one to allow the wolf to mount her and the wolf is referred to as ‘her mate’ rather than the other way around.

While the women in “Bluebeard” and “The Living Book” fell in their predicaments in order to evolve and emerge strong and independent. Matilda was brought up to embrace her own inner power and choose for herself – knowledge passed down from her grandmother:

“Matilda loved spending time with her grand-dam, who taught her herb-lore and told her tales of women who chose to be something other than their outsides might indicate.”

“Red Skein” addresses the fear society exhibits towards change and how firmly it chooses to stick to what is known. Everyone assumes their own role and are intent on not letting go.

“Stick to the path, was the village wisdom. Don’t leave it or you might be lost – worse still, you might be changed. Change was worse than loss; change meant you no longer fitted into your place, you couldn’t be recognized by your own kin, and that was the greatest danger of all.”

In the popular version, veering off the path means certain death in the end, but this retelling places change above death. It’s the bigger evil. It disrupts what’s known and comfortable. The reader is treated to how the village punishes Matilda for her difference; revealed through her mother’s failed attempts to arrange a marriage for her daughter.

The village rejects Matilda.

It is intent on wiping out the change that she brings, erasing the deviation from its genetic pool.

Yet, Matilda is not bothered. Her independence allows her to leave her village in the end – an action and choice only reserved for the men.

—

Chances are not many have come to this point. If you have and this has been something you enjoyed, please donate to my PayPal account. I’ve been reviewing books for more than five years now and this project takes a lot of time and effort. Any appreciation would be grand! If you can’t donate, like and share the post! Comment even.

[…] my search for images for the post on Red Riding Hood for my Friday Story Dissection post, I found some breathtaking imagery dedicated to Red Hood and her story. This sexually charged image […]