After reading Cthulhurotica, the first editorial work by Carrie Cuinn I had encountered, I knew I had found an editor I’d follow into any and every project she would involve herself in. Why? It’s fairly simple. Cuinn doesn’t edit, but rather throws herself with such abandon in her vision as to how her anthologies ought to look, feel and be, the finished product has its own gravitational pull and it won’t let go until you’ve read the last page.

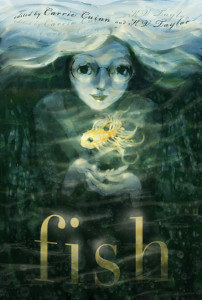

In my Goodread mini-comment, I describe Fish as effortless, dream-like, diverse and exquisite, which certainly holds true as I consider the anthology to be a revelation, because it’s just fish. No restrictions upon genre, no neatly defined prompt to cater to specific tastes. It’s just you and the stories and the fish. Simple and yet so risky. As you read Fish, you step further into a dark and undisturbed ocean where you see reflected light dance across scales and experience ink-black beauty with sharp teeth.

As genius as the anthology is, it’s a tough cookie to review, specifically because the stories have no unifier tohold them together as they dart in different direction not unlike a school of fish, which breaks formation to avoid an attack. I can go ahead and write quasi-deep comparisons to ocean life, but I when I review anthologies I want to mention at least two thirds of the stories. My approach will be to explore the themes in the anthology, so here goes.

As genius as the anthology is, it’s a tough cookie to review, specifically because the stories have no unifier tohold them together as they dart in different direction not unlike a school of fish, which breaks formation to avoid an attack. I can go ahead and write quasi-deep comparisons to ocean life, but I when I review anthologies I want to mention at least two thirds of the stories. My approach will be to explore the themes in the anthology, so here goes.

It comes as no surprise to see the theme of transformation in anthology dedicated to an animal as the opener story by Polenth Blake (“Thwarting the Fiends”) testifies. A small child goes on a mission to explore the tall grass and finds a floating fish that leads him on an adventure. What seems an innocent adventure grows into a bizarre tale of transformation with an ending that has me thinking the pond with talking fish might have claimed more children than one.

Turning into a fish can be a monstrous process, which the self-obsessed Trent discovers in Tim Kane’s unforgiving “Vanity Mirror”. Why he is haunted by a reflection of himself as a humanoid fish trying to escape its mirror prison doesn’t receive an explanation? Where does the fish come? Has Trent switched bodies with it? Is he possessed? Horrible things in life happen without much of a reason and this qualifies as such. You accept it and move on.

Can fish turn into humans? Certainly! Cate Gardner seeks to show you what fish as humans are like once you feed them magic flakes in “Too Delicate for Human Form”. In a typical Gardner fashion, an already weird concept with its haunting, mournful beauty descends into madness as the narrator discovers where exactly her aunt found her supplies of magic flakes. The revelation shatters the narrator’s certainty of the life she has lived so far. Ultimately, this is a sad tale with desperate words and feverish language.

Fish are readily associated with numerous feats and miracles, because they inhabit a world we as land inhabitants have just begun to pierce. Shapeshifting, incarnation, speech and wish granting have been readily ascribed to fish as they symbolize different things to different cultures and the stories in the anthology reflect the shifting roles of fish in storytelling.

A popular image is that of the talking, intelligent fish, which receives several treatments here. Whether it’s granting wishes with hilarious outcome (“Maria and the Fish” by Andreea Zup) or flinging insults that would corrupt your soul (“The Talking Fish of Shangri-La” by Bear Weiter) – admittedly two of the lighter, more upbeat stories – or sharing wisdom (“One Let Go” by Paul A. Dixon), fish prove that they can be on par with humans as soulful creatures. Sometimes, the barriers between species prove impossible to breach (“I Know a Secret” by Shay Darrach) and what the fish have to say remains hidden, while other times fish share their own conversations to benefit those that consider them dull as seen in “The Skin of Her Skin” by Camille Alexa. This last story certainly stands out as one of the more beautifully crafted tales. Alexa uses a delicate language to convey the thoughts of the koi and a wounded tenderness reserved to the eons-old barja fish, whose name meals ‘save’ in Islandic – a key detail in the story itself.

What surprised me is how authors used fish as a symbol for hope and tool for social commentary in the post-apocalyptic tales. In “Never to Return”, Sarah Hendrix portrays a state of complete environmental with no chance to restore the planet to its former stage and in its quiet manner is confirming that a deep-rooted dream will never be fulfilled. “A Salmon Tale, 2072” by Andrew Fuller sees the opposite scenario – the humans have been wiped out, but the wildlife returns and those who do survive help revert the environment back to its original state (magic Shapeshifting salmon included). Perhaps, a prediction as to where we are headed as a species. “Fish Tears” by A. D. Spencer also falls i n line with this theme of restoration and hope falls. This story, in particular, shouldn’t be read about – it should be experienced. It’s moving and beyond beautiful as it deals with revival and awakening in such a raw and organic way.

Then there are the stories that take place outside Earth under the presumption that Earth has died and nothing can live on it anymore. Mike Wood writes about a failed attempt to repopulate the Earth from habitats in space in “The Last Fisherman of Habitat 37” – another quiet take on the end of things and while the project in large has failed, the seed of hope has been sown as the last fish specimens, genetically modified may they be, survive. Ken Liu sees that interstellar travel to a new planet is the solution in his excellent, heart-felt “How Do You Know If a Fish Is Happy?”, which explores how humans and fish can live together in a symbiotic relationship after a slight genetic tampering with interesting side effects as fish are shown to develop emotions and feel loyalty and love.

All titles to this point give fish a modern interpretation, but as we all know, fish have appeared in our lore for centuries and several authors seek inspiration from world culture. T.J. McIntyre tells the lore behind catfish’s appearance in “How Did the Catfish Get a Flat Head, You Wonder?”, a delightful myth presented as a story told from an elder to a young boy. It’s a straight-forward tale with a simple, sparse vocabulary and construction, a stylistic direction both Megan Englehardt and Tracie McBride have adopted for their tribal-tinted stories. In “Anansi and the New Thing”, Englehardt uses the adventure of the spider god Anansi with Fish as a tool to convey wisdom, while McBride uses the image of a Maori amphibian monster to tell three different stories about the same event in “The Touch of Taniwha”.

What I most appreciate about stories derived from an already established cultural narrative is the sense of authenticity. I have grown up on Russian fairy tales, because of Bulgaria’s proximity to Russia’s cultural influence and have found Alex Shvartsman’s “Life at the Lake’s Shore” and Mel Obedoza’s “The Fisherman and Golden Fish” to treat their source material with respect. The two stories are based on the old Russian tale of “The Fisherman and Golden Fish”, one of the most popular stories in Russian folklore. Shvartsman crafts a depressing tale where the protagonist follows the fisherman’s example, catches a wish and makes wishes, but every wish has a heavy price. What makes the story heavy to read is its ties to the events in the country since the Revolution through World War II and the harsh communistic regime. On the other hand, Obedoza doesn’t break from the fairy tale model and has the fisherman become the victim of the golden fish. In the original story, the fish is benevolent, but Obedoza asks what if the fish had a vile heart and the answer to that ‘what if’ leads to a tragic end.

Matthew Bennardo educates readers with a brief catalogue of fish and the function they perform for the community living on North Isles in Scotland. At first glance, there is no story to speak of. The author describes fish as part of people’s lives and creates a sense of normalcy, which then is dispelled once the author reaches the rare monk fish, and suddenly, it’s not the absence of an actual story, but the potential of one that makes “The Fish-Wife’s Tale” enjoyable.

Another instance where mythology bursts into life is H.L. Fullerton’s “The Fish Are There On Land”. Readers step off from the page onto a Hawaiian island, where a messenger awaits his bounty to take uphill where a feast must be prepared with the day’s catch from the ocean. What happens when the fish he holds in his hands turns out to be a god? Nothing good. Finally, no anthology can be complete without an entry about Japan. Timothy Nakayama treats readers to Japanese koi demons in “Fallen Dragon”, another story told as a relation of events from one character to another, which turns out to be a preferred narrative choice.

I found this technique to be highly pleasurable to experience, because the act of telling a story is a powerful thing on its own. Even presented in written form, it brings us back to our childhood story time as well as the sense of wonder. Fish exemplifies sense of wonder and the beauty in it as shown in the dark, murky Lovecraftian effort by Amanda C. Davis, “O How the Wet Folk Sing”, and the wide-eyed, innocent and uplifting “Lanternfish In the Overworld” by Suzanne Palmer. Then, you can read of the most amazing steampunk heroine and golem fish in “Water Demons” by Jennifer R. Povey, the boyfriend with a fishbowl for a head in “Fisheye” by Maria Romasco-Moore and Claude Lalumière’s bizarre courtship and marriage in “Xandra’s Brine”.

I’m reaching the point, where I point out a name and a title and marvel at what makes it special to be included, but that’s not what I’m after with this review, so I will conclude even though I haven’t mentioned every single entry. That’s fine though, because the rest of the exploration is up to you. I have made my point. Carrie Cuinn and K.V. Taylor reveal to you an ecosystem of underwater wonders that’s outrageous, eclectic and beautiful. Theoretically, some might suspect it shouldn’t be able to work as there is nothing at first glance to hold these stories together, but there is so much soul in the project to cement this as the definitive anthology for 2013 – at least in my book.

[…] He goes on to look at many of the stories in depth, offering mini-reviews of about 2/3 of the book’s contents. You can read the rest of the review here. […]