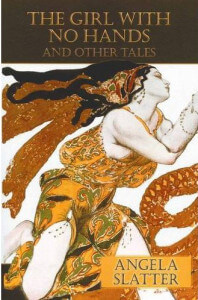

Title: “The Girl with No Hands & Other Tales”

Author: Angela Slatter

Genre: Fantasy / Fairy Tale / Lore

Pages: 210

Type: Collection

Stories: 16

—

What’s Friday Story Dissection?

It’s a weekly feature on the blog where I cast a more in-depth look into short stories, either in a collection or in an anthology. The idea is for these short stories to exist within the context of a loose narrative, determined by a theme, intent and story order intended by author or editor.

Anthologies have adopted detailed prompts to narrow down the wiggle space of submissions, thus creating a more focused narrative. I believe short story collections tell a larger story with individual stories feeding off and layering a top each other.

It’s my intent to break down stories to their elements – a detailed, spoiler-full review with the mandatory quotes as a base to speak about the short story collection/anthology at length. This is a practice Bulgarian literature teachers would implement, loosely translated as “analytical literary essay”, but on a much smaller scale. Plus, I intend to weave in personal digressions, so there’s that, too.

—

Stories Dissected:

[1] “Bluebeard”

[2] “The Living Book”

[3] “The Jacaranda Wife”

[4] “Red Skein”

—

“The Chrysanthemum Bride” by Angela Slatter (5/16)

The first four tales I’ve written about concern the carnal, the romantic and the insidious in the relationships between men and women. These stories address a power balance which has been in place for centuries and redraws the lines with such ease the shift barely ripples the narrative known to so many. From the courtesan mother in “Bluebeard” , who kills to protect her child, to a werewolf Red Riding Hood in “Red Skein”, women disrobe from societal expectations, peel off the mold and stand bloodied, raw and powerful.

Fashion Spread, but I couldn’t find the right information

“The Chrysanthemum Bride” gives Slatter the necessary setting and platform to examine the unsavory fates allotted to women who embody the traditional female virtues – beauty, grace, poise and submission – and deconstruct the ‘happy ever after’ moment that comes to virtuous and beautiful girls who meet their prince. What better way to do so than in ancient China with its overcomplicated hierarchy and intricate cultural structure compromising of rituals, customs and rules.

Predominantly, “The Chrysanthemum Bride” explores beauty – its presence and its absence, its weight and its price – through the lives of two sisters, Mei-Ju and Chen-Ju. Although have the same blood and the same heritage, Mei-Ju is beautiful whereas her sister is plain. It’s not a pretty sisterly relationship as beauty serves as a divide where one stands above the other. The simple fact Mei-Ju possesses startling beauty warrants a special treatment:

“She is sleek but a little plump; any spare food goes to her, to keep her beauty intact, for her family believe this is how she will save them. If she is lovely enough, a rich man will take her as wife or concubine, then, they pray, prosperity will flow to them, that emptiness will become full again.”

For Mei-Ju’s family, beauty equals salvation. It equals a less exhausting, less cruel life and it shows. In her youth, having shown signs she’d blossom, her family broke and bound her feet so that she could have the so-called “lotus feet” – the preferred beauty standard at the time. A rather painful procedure that renders the girl in question a visually pleasing invalid who can’t work or run away – a possession to marvel.

“A Painting of a Chinese Bride” by Jiang Changyi

The dehumanization in the name of beauty prevails within the story. Mei-Ju doesn’t show any other qualities within her other than an outer beauty. Her beauty has become an entity itself and it dictates the social politics within her family. Within the story, it’s shown how Chen-Ju has assumed the role of a servant to her sister, while working in the field, whereas Mei-Ju has been freed from all labor and duties.

Mei-Ju is the prized family relic – polished, perfected, preserved and primed for sale. Despite her hatred, even Chen-Ju recognizes the power beauty wields:

“Clenching her firsts, Chen-Ju had fought the urge to hit, fought the urge to disfigure. She, too, believed that the cost of a future would be paid in the currency of Mei-Ju’s face.”

Further in the story, we see Mei-Ju finally obtain a higher status as a bride-to-be to the Crown prince himself no less. She goes through what would be pivotal moment in any Disney movie, the makeover. She sheds her former life and dons new dresses, new jewelry, new makeup and in the end, she becomes a princess, an ornament herself, impractical and immobile.

“She feels weighted down by her finery but she does not care; it is a burden she embraces, a weight she craves.”

Yet, the cruel truth is that her marriage for the Crown Prince is not to be consummated in life, but one that will be spent in the afterlife as the Crown Prince has been dead for years now and Mei-Ju is to follow him on their wedding. This is the true price of beauty.

Where Mei-Ju suffers an untimely end, everyone else has benefited from the trade-off. Chen-Ju has risen in rank thanks to the connection with the royal family and now has married into a more prosperous family. Mei-Ju’s parents have been provided for until they die. The Empress is happy for her son will now move wedded as per tradition. The sale has been successful and everyone is happy except for Mei-Ju for she isn’t a fully realized character but a vessel for her virtue.

This is the warning Angela Slatter writes. Beauty for beauty’s sake strips you from humanity and you become objectified – a still prevailing attitude even today. It’s no wonder the story ends with Mei-Ju appearing as a spirit caught in the bronze mirror, which has been passed from Mei-Ju’s concubine grandmother down to the beautiful girl in the family:

“Chen-Ju keeps the mirror for a month, until the day Mei-Ju’s face appears in it. Chen-Ju is transfixed by her sister’s hair, red-rimmed, weeping eyes, her mouth in a constant ‘o’ of despair. […] Chen-Ju wates for a while, then wraps the thing in a piece of old cloth. She sneaks out of her parents’ house, makes her way to a fields and buries the mirror and her screaming sister as deeply as she can. Chen-Ju’s heart lifts; she does not bear the burden of beauty and for once she is grateful.”

The ending speaks for itself as Angela Slatter lays out the truth about beauty without much of a commotion. In a sense, “The Chrysanthemum Bride” comes close to the “The Jacaranda Wife” for both heroines are punished for their demure beauty with cruel marriages, but while Emily became an accidental victim for she didn’t belong in the human world, Mei-Ju strived for a royal marriage.

It was her ambition to use her beauty and only her beauty to reach the top of the hierarchy that eventually led to her undoing. In a sense, both characters represent the polar opposites of the same archetype.

—

Chances are not many have come to this point. If you have and this has been something you enjoyed, please donate to my PayPal account. I’ve been reviewing books for more than five years now and this project takes a lot of time and effort. Any appreciation would be grand! If you can’t donate, like and share the post! Comment even.

[…] [1] “Bluebeard” [2] “The Living Book” [3] “The Jacaranda Wife” [4] “Red Skein” [5] “The Chrysanthemum Bride” […]